Published in the June 2008 issue of Himal – Uneasy dreams of Bundi

***

If, today, Rudyard Kipling were to come back to Bundi, in Rajasthan, he would find that nothing has changed in nearly a century since he last was here. Indeed, traveling to Bundi is a bit like traveling back in time – except that our time machine has to be a decrepit taxi hired from nearby Kota. After hours of shallow breathing, trying to escape the industrial fumes of Kota and the heat and dust of the road, we finally enter a town the beauty of which not only seems to be from another era, but from another place altogether.

For centuries, the tour groups have come, seen and conquered nearly all of Rajasthan, from pink Jaipur to golden Jaisalmer. But they have continued to ignore brown, sandy Bundi with a vengeance. Perhaps for that reason the town’s rough charm remains undiminished. Tucked neatly into a valley at the foot of the Aravalli Range, the town remains a figurative crevice in the fold of time.

As we take the last bend in the road, the first thing to greet our eyes is the Taragarh Fort, looming large in the distance. The same sight must have greeted Kipling (whose name crops up regularly in discussions around the town) as he entered Bundi, which he described as “an avalanche of masonry ready to rush down and block the gorge.” Bundi, believed to have been established in the mid-13th century by the Rajput chief Rao Deva, must have held the same allure for Kipling that it does for today’s visitors, most of whom stumble upon it by happy chance.

Water is the most precious commodity in the desert, and there are elaborate ways to access it. Bundi is rightly famed for its 50-plus stepwells. Traditionally, these baolis were not just reservoirs, but also served as bathing places and social hubs – places to meet, chat and catch up on the news of the royalty. Today, most of the baolis have dried up, but it nonetheless seems logical to start our explorations of Bundi from one of them. And so, we head to the most famous of all of the stepwells, the raniji ki baoli, where the queens would have bathed eons ago.

The gate to the well is locked, and the watchman is asleep under a tree when we arrive just after noon. He slowly comes back to life as we shake him awake, his breath reeking of alcohol. He informs us that visitors are no longer allowed to see the baoli, that the gate will remain locked, and would we mind going away to leave him to sleep in peace? But we have not come so far in the heat to be turned away so quickly, and our questions flow out fast and furious – though they are all answered outside of the locked gate.

Built in 1699 by and for Rani Nathavatji, the watchman tells us, this 46-metre-deep baoli is one of the largest in the area. It is said to have served as a private swimming pool for the royal ladies, a fact illustrated by the exquisite arches and carvings that seem too elaborate for a mere commoners’ water source. But today, the stepwell is dry, and bears few signs of ever having held enough water for the entire kingdom. Even without water (and even if we are forced to peer through the locked gates), Raniji ki Baoli presents a pretty sight, with flocks of pigeons suddenly taking flight from the arches as we prepare to leave.

Dry and drying stepwells not withstanding, water is everywhere in Bundi, with young and old alike sitting on the roads ladling out cool drinking water to locals and tourists. “People pay whatever they wish,” one young woman vendor says. “Though sometimes they don’t pay anything at all,” she adds wistfully.

Left to the goblins

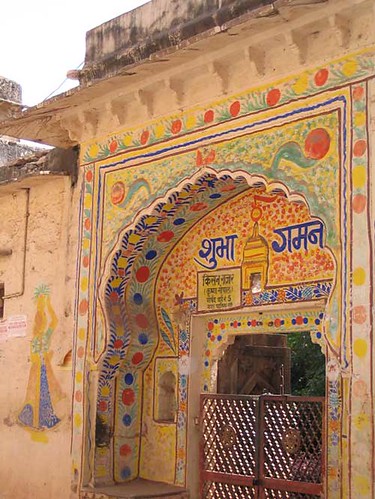

Kipling wrote that the Garh Palace, on the hillside next to the fort, was “such a Palace as men build for themselves in uneasy dreams – the work of goblins rather than of men.” What is all this about goblins, I wonder silently as we make our way slowly up the steep cobbled path to where the palace is. The path itself must have been rough once upon a time, but has been trampled into a resigned smoothness by the feet of elephants and infantry over the centuries. Inside the palace, there is again a feeling of time travel, more acute than ever. The arched windows offer glimpses of the town in the distance, the pool filled with water and algae in equal measure, with a tiny chhatri, or pavilion, in the middle of it all.

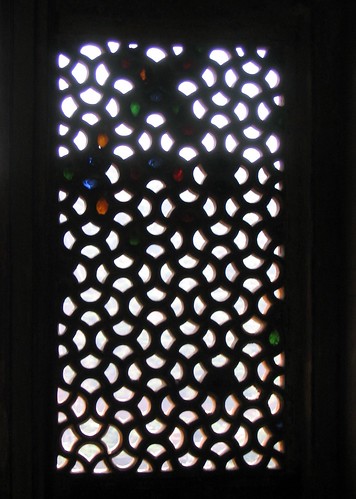

There is no one else at the palace, and our voices and footsteps echo through the empty chambers. We walk into a room that is usually darkened and locked, but is opened for particularly insistent visitors such as ourselves. Every inch of space on the walls and ceilings is filled with intricate floral designs, the colour spilling out from the walls and filling the senses. Sunlight peeps in through broken stained-glass. There are also scratch marks and some obnoxious graffiti on the beautiful murals, which most likely explain why much of the palace is shut to visitors.

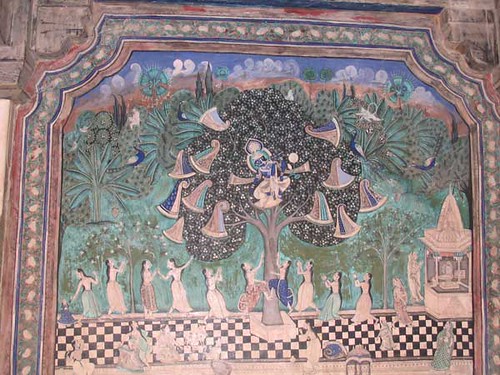

Thankfully, the most captivating part of the palace, the chitra shala or ‘chamber of paintings’, is wide open – an entire section of the palace devoted to the miniature artworks of the Bundi School. There is no single theme across these paintings, and that perhaps makes them all the more interesting. While most depict scenes from Krishna’s life story, the raas-leela, there are also a number of pieces on the various splendours of the Bundi kingdom – snippets of court life, animals of the area, hunting scenes – all done in the blues, aquamarines and turquoises that are associated with paintings from this area. The predominance of these colours makes one wonder whether these hues, too, are a reference to the romance with water in this parched land.

After leaving the painting chamber, we scramble up the thorny path to Taragarh Fort – or, at least, what remains of it today. Named for its star shape, the fort was built in the mid-14th century, and was never conquered. Standing on the battlements – isolated on top of a hill, overlooking the town on one side and the roads leading in and out of Bundi on the other – it is easy to understand why it was never captured. But what the invaders could not do, time has. The fort’s impenetrable walls have crumbled in large parts, and the palace exudes a sense of abandonment, as if all the people left in a hurry. There are several massive cannons here rusting, and the fort’s stepwells too are mostly dried out.

Amidst Taragarh’s ruins, too, there are no humans present, only langur monkeys and pigeons. As we walk past through the overgrown shrubs and dry vegetation surrounding the fort, down the path towards the town, I can faintly hear Kipling’s goblins laughing in the distance, as they scamper back to their secret hideouts in the many tunnels inside. I know I am imagining it; but in this place and at this time, it is easy to believe.

One thought on “Uneasy dreams of Bundi”